The Football Association, English football’s governing body, was formed in 1863. ‘Organised football’ or ‘football as we know it’ dates from that time.

Ebenezer Morley, a London solicitor who formed Barnes FC in 1862, could be called the ‘father’ of The Association. He wasn’t a public school man but old boys from several public schools joined his club and there were ‘feverish’ disputes about the way the game should be played.

Morley wrote to Bell’s Life, a popular newspaper, suggesting that football should have a set of rules in the same way that the MCC had them for cricket. His letter led to the first historic meeting at the Freemasons' Tavern in Great Queen Street, near to where Holborn tube station is now.

The FA was formed there on 26 October 1863, a Monday evening. The captains, secretaries and other representatives of a dozen London and suburban clubs playing their own versions of football met “for the purpose of forming an Association with the object of establishing a definite code of rules for the regulation of the game”.

The clubs represented were: Barnes, War Office*, Crusaders, Forest (Leytonstone), No Names (Kilburn), Crystal Palace**, Blackheath, Kensington School, Perceval House (Blackheath), Surbiton, Blackheath Proprietory School and Charterhouse.

*Civil Service FC, who now play in the Southern Amateur League’s Senior Division One, are the only surviving club of the eleven who signed up to be FA members at that first meeting in 1863, when they were listed as the War Office. Civil Service FC are also celebrating their 150th anniversary in 2013.

**This club has no connection with the present Premier League club.

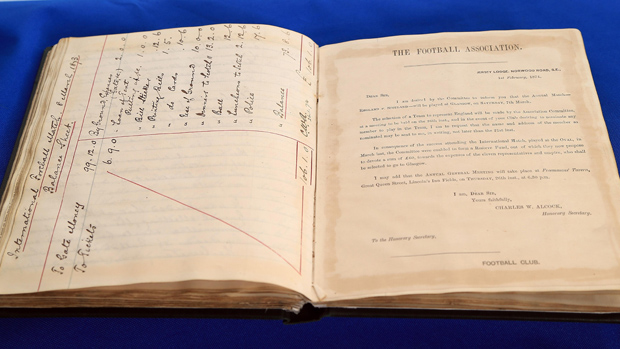

There could be no authority without laws and six meetings took place in 44 days before the new Association could stand on its own feet. The FA was formed at the first. Its rules were formulated at the second. (There was an annual subscription of a guinea and alterations to rules or laws were to be advertised in sporting papers.) A useful discussion on drafting the laws took place at the third.

‘Football’, they thought, would be a blend of handling and dribbling. Players would be able to handle the ball: a fair catch accompanied by ‘a mark with the heel’ would win a free kick. The sticking point was ‘hacking’, or kicking an opponent on the leg, which Blackheath FC wanted to keep.

The laws originally drafted by Morley were finally approved at the sixth meeting, on 8 December, and there would be no hacking. They were published by John Lillywhite of Seymour Street in a booklet that cost a shilling and sixpence. The FA was keen to see its laws in action and a match was played between Barnes and Richmond at Limes Field in Barnes on 19 December. It was a 0-0 draw.

Bryon Butler wrote in an Official History published in 1991: “The FA’s early influence on the game at large was not dramatic or even widespread. Its membership was small and its authority and laws were often challenged and sometimes ignored. But its motives and ambitions were so honourably based that, like growing ripples on a still pond, its standing grew perceptibly. It was a period of high ideals and ready compromise”.

The move which probably did most to broaden the outlook of the FA and spread its influence over a wider field was made at a meeting at the office of The Sportsman newspaper on 20 July 1871. The announcement of the birth of ‘The Football Association Challenge Cup’ ran to just 29 words: “That it is desirable that a Challenge Cup should be established in connection with the Association for which all clubs belonging to the Association should be invited to compete”.

‘The Cup’ was the idea of one man. Charles Alcock, then 29, had been The FA’s secretary for just over a year when he had his vision of a national knockout tournament. He had remembered playing in an inter-house ‘sudden death’ competition during his schooldays at Harrow and his proposal was swiftly agreed.

The rules of the new competition were subsequently drafted and the entries of these 15 clubs were accepted: Barnes, Civil Service, Crystal Palace, Clapham Rovers, Hitchin, Maidenhead, Marlow, Queen’s Park (Glasgow), Donington Grammar School (Spalding), Hampstead Heathens, Harrow Chequers, Reigate Priory, Royal Engineers, Upton Park and Wanderers.

It was a disappointing entry, because the FA had 50 member clubs by that time. Apparently, many of them felt that competition would lead to unhealthy rivalry and even bitterness. The first Cup season turned out to be quite truncated with withdrawals and byes. Only 12 clubs actually played and there were just 13 matches in total but Wanderers beat Royal Engineers 1-0 before 2,000 spectators at Kennington Oval in a Final described by The Sporting Life as “a most pleasant contest”.

A match between ‘England’ and ‘Scotland’ was another good idea from Alcock. He wrote to The Glasgow Herald on 3 November 1870 to announce that such a fixture would be played at the Oval in 16 days’ time. “In Scotland, once essentially the land of football, there still should be a spark left of the old fire”, he said. ‘England’ won this unofficial international 1-0 and all the players, English and Scottish, lived in London.

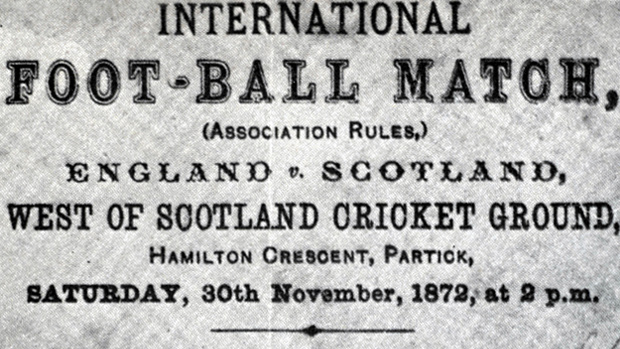

The Scottish FA hadn’t yet been formed but the Queen’s Park club agreed to organise the first official international between England and Scotland. It took place at Hamilton Crescent, the Partick home of the West of Scotland Cricket Club, on 30 November 1872. The admission fee, as it had been for the first Cup Final, was a shilling. A 4,000 crowd, including a good number of ladies, was present for a 0-0 draw that Bell’s Life saw as “one of the jolliest, one of the most spirited and most pleasant matches that have ever been played according to Association rules”.

County and District Associations, charged with fostering the game and organising clubs in their own areas, sprang into life all over the country between 1875 and 1885. They ran their own Cup competitions, inspired enthusiasm and provided the framework for hundreds of new teams. The FA was now truly a national body.

Some clubs in the north, enamoured with the FA Cup, saw nothing wrong in profit and success or in paying a man for doing his job. It led them away from the concept of amateurism, cherished by clubs in the south, and it forced the FA to formally legalise professionalism in 1885. A year earlier it had seemed that English football was on the brink of chaos, with a ‘British Football Association’ having been formed as a rival to the FA.

William McGregor, an Aston Villa committee man and FA stalwart, recognised that football had an urgent need for an organised system of regular fixtures involving the top clubs. He wrote to some of those clubs about a league format for football and a ‘Football League’ with 12 clubs came into being after just two meetings in 1888. The FA was still the ultimate authority but the League would live as a self-contained body within it.

William Pickford, later the FA’s president, summed it up: “The power of the League strengthens the Association and the authority of the Association safeguards the League”.

The professionals’ contribution to the popularity and development of the game continued to grow and this was openly resented by the diehard amateurs. The FA directed County Associations to affiliate the professional clubs within their areas and this was the final straw for Surrey and Middlesex who refused to accept them. There was an ‘amateur split’, lasting from 1906 to 1913, and an ‘Amateur Football Association’ was formed to make a stand against the ‘corruption’ of the game.

Their clubs and players couldn’t play ‘with or against’ those under the jurisdiction of the FA and this meant that they were banned from taking part in the FA Cup and The FA Amateur Cup. It was surprising that the division lasted as long as seven years but, in the end, it only reinforced the authority of the FA.

The FA appeared quite indifferent to the growth of football abroad. In 1902 the Netherlands FA suggested European unity, an international championship and uniformity of the laws in all countries.

When the French mooted a ‘European Federation’, they received this reply: “The Council of the Football Association cannot see the advantages of such a Federation, but on all matters upon which joint action was desirable they would be prepared to confer”.

England weren’t one of the original members of FIFA, founded in Paris in 1904, but within two years the FA had ‘formally approved’ the existence of the new body and sent a powerful delegation to a FIFA conference in Berne. Daniel Woolfall, from Lancashire, was elected FIFA president.

The FA was widely criticised for permitting the 1914-15 FA Cup competition to run its course after the First World War had begun. The Dean of Lincoln, in a letter to The Times, wrote disparagingly of “onlookers who, while so many of their fellow men are giving themselves in their country’s peril, still go gazing at football”. It was undeserved. The FA had taken advice from the War Office, who agreed that the continuation of football – if only to the end of that season – would boost morale.

Wembley, a north-west London suburb, had been chosen as the site for a British Empire Exhibition. The FA were advised that the centrepiece would be ‘a great national sports ground’ and a quickly convened ‘Ground Committee’ signed an agreement in May 1921 to stage the FA Cup Final there for the next 21 years. The stadium took 300 working days to build and was completed just four days before the 1923 Final between Bolton Wanderers and West Ham United.

The new stadium’s official capacity was 127,000 but the crowd that descended on Wembley that April afternoon could have been twice that number. FA secretary Frederick Wall said to King George V: “I fear, Sir, that the match may not be played. The crowd has broken in. The playing-ground is covered with people”. Chaos slowly turned to order, with His Majesty standing patiently in the Royal Box, and the match finally got under way 45 minutes late.

It was decided that all future Cup Finals would be by ticket only.

The first World Cup was held in Uruguay in 1930 but the FA didn’t enter a team. England had only played against the other Home Associations before making a tour of Austria, Hungary and Bohemia in 1908. The World Cup might have provided a useful examination of the strength of the British teams but they had withdrawn from FIFA, the competition’s organisers, over the thorny question of ‘broken time’ payments to amateur players.

However, one important link was maintained. The ‘International FA Board’, the guardian of the game’s laws since 1886, had originally consisted of two members from each of the four British Associations. Two FIFA representatives were added in 1913 and their retention after the split guaranteed the continuing authority of the Board and kept an important channel open for future negotiation.

Six days after the 1934 Cup Final, which he refereed, Stanley Rous was one of six candidates interviewed at 22 Lancaster Gate for the job of FA secretary. His appointment was confirmed two months later and he immediately set about improving and streamlining the FA’s routine and procedure. Courses were developed for referees and coaches, which soon had a beneficial influence in clubs, colleges, schools and youth organisations.

Rous, the former master at Watford Grammar School who had already introduced the ‘diagonal system’ of refereeing, also used his expertise to rewrite the laws of the game. They were a little disjointed and Rous’s clearer version of the 17 laws of football was accepted by the International Board in 1938.

Football, like everything else, was affected by the political troubles of the 1930s. Germany and Italy in particular saw sport as a vehicle for propaganda and so too, in a more subtle way, did the British Foreign Office. It was made clear to the FA which countries it should avoid visiting and which countries should always face the strongest side that England could put together.

England edged the Italians, then World Cup holders, 3-2 in the notorious ‘Battle of Highbury’ in 1934 and it merely served to confirm English football’s opinion that it was the best on the planet. Four years later, with war only 16 months away, England met Germany in Berlin’s Olympic Stadium and beat them 6-3. On the British ambassador’s advice the England team controversially gave the Nazi salute during the playing of the German national anthem.

During hostilities the FA co-operated with the War Office and the Board of Trade, the armed forces, Civil Defence, the Red Cross and St John’s Ambulance and the Central Council of Physical Recreation. Coaches, trainers and players knocked the country’s young men into combat shape. Nearly 200 football grounds became centres for a ‘Fitness for Service’ campaign, organised by The FA and CCPR, in which more than 40,000 took part.

There was no FA Cup or Football League during the war but there were knockout tournaments of every size, district and regional leagues, service competitions, charity matches, representative and international matches. It all took place on the understanding that it didn’t interfere with the more serious business of winning the war. Post-war football was seen as an antidote to austerity and crowds flocked to the grounds. A staggering 41.3 million watched League football in one season.

The FA looked to the future. In 1946 it offered help to clubs and associations at all levels with coaches, courses, text books, publicity and – as and when funds became available – loans and grants. The decision was also taken to rejoin FIFA, a decision made easier by a new sense of European unity after the war. At Rous’s suggestion a Great Britain team played a celebration match against the Rest of Europe in Glasgow, with the £30,000 proceeds going to the impoverished FIFA.

Rous was convinced that the FA needed an expert on its staff. On his prompting Walter Winterbottom, a Wing Commander in charge of physical training at the Air Ministry, was appointed ‘Director of Coaching’ and ‘England Team Manager’. There was some initial resistance from the FA Council but they were swayed by the fact that the former Manchester United half-back would be doing both jobs for one salary.

Winterbottom went on to build a national coaching scheme which became the envy of the football world. He built a network which, by way of new standards, enlightened technique and an ever-widening circle of coaches, reached into schools, clubs and associations in every corner of the country. England’s first manager, admired for his tactical knowledge, was able to argue his preferences but the team was still chosen by a committee.

England were one of the top teams in the world. With a star-studded forward line of Stanley Matthews, Stan Mortensen, Tommy Lawton, Wilf Mannion and Tom Finney they rattled in ten goals against Portugal in Lisbon and then beat the powerful Italians 4-0 in Turin. They were one of the favourites to lift the Jules Rimet Trophy at the 1950 World Cup in Brazil.

England won their first-ever World Cup Finals match, 2-0 against Chile in Rio’s huge Maracana Stadium, but the next – played nearly 300 miles to the north in Belo Horizonte – brought an embarrassing 1-0 defeat to the 500-1 outsiders, the United States. After another loss, 1-0 to Spain back in Rio, England were on their way home. At least the Final referee was English.

The FA, a target for criticism, set up a technical committee which sought the opinions of directors, managers and players, past and present, at a series of meetings. Coaching, training, preparation, the development of young talent, systems, tactics and refereeing were among the topics discussed. The result was a generally better relationship between the FA and the clubs, who now understood each other’s problems and priorities.

The year of the FA’s 90th anniversary, 1953, saw two Wembley matches that would live long in the memory. Stanley Matthews, the ‘Wizard of the Dribble’ and a genuine sporting hero, finally collected his FA Cup winners’ medal after Blackpool’s 4-3 win over Bolton Wanderers in what, arguably, is still the competition’s most exciting Final. Matthews, who had appeared on the losing side in two previous Finals, was then 38.

Six months later England were humbled 6-3 at Wembley by Hungary, the Olympic champions who hadn’t lost a match for three years. They were the first Continental team to beat England at home, the manner of their victory proving beyond doubt that the country which had ‘invented’ football was now struggling to understand its finer points. The Hungarians showed their superior skill and teamwork again as they crushed England 7-1 in Budapest in 1954.

Stanley Rous wrote: “Organisational developments have usually followed events instead of shaping them and the evolution of the whole football system has been, to say the least, haphazard. At Lancaster Gate we are usually thought of as a governing body; I think we should prefer, as far as possible, to be thought of as a body that is always ready to learn”.

Winterbottom wanted more time with his players and a format for building a team, instead of simply having eleven players selected for him on a match to match basis. The FA’s technical sub-committee concluded that “a great deal more can be done towards bringing England players and teams to a high standard of performance in the next four years”. Initial team selection in future would be by Winterbottom and just two members of the selection committee.

After the 1958 World Cup in Sweden, at which an England team missing some Manchester United stars due to the Munich tragedy failed to progress beyond the first round, English football moved towards a period of substantial change. The FA agreed to recognise Sunday amateur football in 1960 and the League Cup was introduced in the same year. “The FA Cup is football’s Ascot, the League Cup is its equivalent of Derby Day at Epsom”, said League secretary Alan Hardaker.

Stanley (now ‘Sir Stanley’) Rous became FIFA president in 1961 and thought that Winterbottom should succeed him as FA secretary. However, there was a body of opinion within the organisation that no secretary should again be allowed to get himself into such a position of power and authority. The job went to Denis Follows, the FA’s honorary treasurer and a Council member for 14 years. Winterbottom left to become general secretary of the Central Council of Physical Recreation.

The FA’s centenary was celebrated in 1963 with a banquet, tributes and gifts, memories and visions of the future and, of course, tournaments and matches. The highlight was a Wembley meeting (on 23 October, close to the day of formation) between England and a ‘Rest of the World’ team selected by FIFA. England won 2-1 before a capacity crowd of 100,000.

It took the FA nearly six years to organise the 1966 World Cup, the eighth in history and the first hosted by England, and Alf Ramsey and his players six matches and 20 days to win it. It was the first tournament to receive major television coverage: the global audience for the 32 matches was estimated at two billion and seven out of every ten people in England followed its progress on their screens.

An England team containing world-class players like Gordon Banks, Bobby Moore and Bobby Charlton and determined to ‘play for Alf’, kept clean sheets against Uruguay, Mexico, France and Argentina before edging Eusebio’s Portugal 2-1 in a very sporting semi-final.

Ramsey, who won 32 caps and was England’s right-back against Hungary in ’53, had declared soon after his appointment that England would win the World Cup. He was proved right on 30 July, a day of sunshine and showers, as England beat West Germany 4-2 after a highly eventful two hours’ football. HM The Queen handed the trophy to Moore, England’s unflappable skipper.

Ramsey had managed ‘unfashionable’ Ipswich Town to the League Championship in 1962 and he took the England job on the understanding that he had full control over selection. The old convention of selection by committee passed into history. The new ‘England manager’ was responsible for the Senior, Under-23 and Youth sides, while Allen Wade, a lecturer in physical recreation at Loughborough College, was chosen as the FA’s Director of Coaching.

The ‘Chester Report’ was published in 1968, the findings of a Government enquiry “into the state of Association Football at all levels including the organisation, management, finance and administration”. It recommended that FA Council members should retire at 70. It questioned whether a Council of more than 80 members could be an effective policy-making body and recommended a smaller committee for central policy and planning.

The Report urged that the FA should make greater use of experts on its committees and that rules prohibiting former or current players from administering the game should be abolished. It also suggested that the FA should contribute more from its income to the County Associations and more extensive coaching facilities. Lancaster Gate responded: “It is not expected that a body of this kind (the Chester Committee) can fully understand the ramifications of the complex Football Association. It is not surprising, therefore, that the FA does not accept some of the criticisms”.

However, the FA acknowledged that Norman Chester’s Report deserved serious study. A decision to form an ‘Executive Committee’ had actually been taken at the previous Summer Meeting and a sum of £200,000 was soon earmarked for the Counties.

Sir Alf Ramsey’s England team went to Mexico in 1970 with a realistic chance of retaining the World Cup, despite the heat, the altitude and a lot of Mexicans who wanted Brazil to win it (after Mexico, of course). But they lost bizarrely to West Germany in their Leon quarter final, 3-2 after being 2-0 in front. It was one of those days when everything went wrong. Almost inconceivably, it turned out to be England’s last World Cup Finals match for 12 years.

The next tournament would be hosted by West Germany and Sir Alf’s charges had to beat Poland at Wembley on 17 October 1973 to qualify. In an extraordinary match England forced 26 corners to their opponents’ two, hit post and bar, and came up against a goalkeeper who chose that night to give the most remarkable performance of his career. Jan Tomaszewski saved or blocked English shots and headers with almost every part of his body as the Poles secured the 1-1 draw that took them – and not England – to the ’74 Finals.

The FA’s International Committee assured the England manager that he had their “unanimous support and confidence” but three months later a sub-committee was formed “to consider our future policy in respect of the promotion of international football”. On 8 April 1974 FA chairman Sir Andrew Stephen informed the Executive Committee that “the special committee had unanimously agreed that the engagement of Sir Alfred Ramsey as team manager be terminated”.

Missing out on the World Cup was a disaster. Alan Hardaker summed it up: “The financial loss to the FA caused by England at higher levels could not be ignored. Profits from this source are now so important to the health of the FA, and its contribution to the game at all levels, that our national body has become rather like a football club. It is a business in which profit and loss are closely related to victory and defeat”.

Ted Croker, a former Charlton Athletic player who had become a successful businessman, replaced Follows as FA secretary in 1973. Seeing things with a fresh eye, he quickly decided to make it easier for the man in the street to buy a ticket for England matches. “The FA telephone number was ex-directory”, he was to say, “and trying to get tickets was as hard as trying to get into MI5”. Soon after Sir Alf’s departure he received a call from Don Revie, expressing an interest in the England job.

The former Leeds United boss was to have an unhappy time in charge of the national team. He was criticised for both his defensive caution and his lack of continuity in selection. He used 52 players in his 29 matches, awarded 29 new caps and only once fielded an unchanged side. He was also criticised by the players for his ‘dossiers’ on the opposition which he had seen as essential bedtime reading. England would miss out on another World Cup, hosted by Argentina in 1978, but Revie resigned long before that to become ‘football supremo’ in United Arab Emirates.

Sir Harold Thompson succeeded Andrew Stephen as FA chairman in 1976. He had been a Professor of Chemistry at Oxford University, where one of his pupils was Margaret Thatcher. After the war he founded Pegasus FC, a team of Oxford and Cambridge students which entered The FA Amateur Cup and won the 1951 and 1953 Finals before capacity crowds at Wembley.

By the 1970s the FA was only too aware of the existence of ‘shamateurism’ in English football. It knew that some players who claimed to be ‘amateur’ were being paid by their clubs. The solution, in 1974, was for the FA Council to abolish the official distinction between ‘amateur’ and ‘professional’ players. It meant the end of The Amateur Cup, the England Amateur Team and the Great Britain Olympic Team. The best of the Amateur Cup teams would now play in the FA Trophy; many of the others entered a new competition – the FA Vase.

Ron Greenwood, West Ham United’s manager for 13 years, acted as England’s caretaker boss for the last three matches of 1977. “I saw my task quite clearly”, he said. “I was going to help restore faith and dignity in our game and prove to the world that we could play a bit.”

It was a difficult time for football. Hooliganism was spreading; overdrafts at clubs were growing; television was becoming a thorny issue; players were threatening industrial action over freedom of contract. ‘Football hooliganism’, visible since the late ‘60s, was now a major problem. There was fighting on the terraces, obscene chanting and missile-throwing and there were pitch invasions. The FA chairman thought it was due to “unsettled social conditions, the bad health of the nation and a lack of teaching of values, virtues and discipline”.

The Government blamed the football authorities for failing to take firm measures but the men who ran the game were hardly law enforcement officers. Fences and cages were erected; fans were searched and segregated; CCTV was introduced; the sale of alcohol was limited. The distribution of tickets was carefully monitored, with The FA establishing its own ‘Travel Club’ to control the movement of England supporters abroad.

Greenwood was made permanent manager at the end of 1977 – preferred to Brian Clough, ‘the people’s choice’ – and his team qualified for the 1980 European Championship in Italy and the World Cup in Spain two years later. He had actually announced his retirement to the players after a World Cup qualifier in Hungary but they had talked him out of it on the tarmac at Luton airport.

England were unbeaten in their five matches in Spain, their defence only breached once, but they went out after two 0-0 draws in the Second Round. This time Greenwood really did retire and Bobby Robson, Ipswich Town’s manager for 13 years and a senior member of Greenwood’s coaching team, was the unanimous choice as successor of new chairman Bert Millichip and his small selection committee.

Robson had two roles. He was National Coach too and found himself immediately involved in a major development. After many years of planning ‘The Football Association GM National School’ was opened at Lilleshall Hall in Shropshire by the Duke of Kent on 4 September 1984. Twenty-five of England’s best 14-year-olds, chosen from a list of recommendations from scouts all over the country, began a two-year residential course. With a new intake each September, they were expertly coached at football at Lilleshall and formally educated at nearby Idsall School.

The ‘National School’ was in good hands, with Dave Sexton as Technical Director and Denis Saunders as Principal. The boys’ development was carefully monitored, demands on them were controlled and their experience was broadened by representative football. Many didn’t fulfil their promise; many played at Football League level; one of them (Michael Owen) scored 40 goals for England.

There were more than a hundred licensed Centres of Excellence for promising youngsters between the ages of 11 and 14, many of them at professional clubs, and also non-residential ‘Soccer Funweeks’ for boys and girls aged between eight and 13 at sports centres all over the country. Qualified coaches ran them and stars of the game made guest appearances.

In the late ‘80s English football suffered the horrors of Bradford, Heysel and Hillsborough. Lord Justice Peter Taylor’s report after the Hillsborough tragedy of 1989, when 96 supporters died at an FA Cup Semi-Final, was a plan for the radical modernisation of grounds which signalled, amongst other things, the coming of ‘all-seater’ stadiums. The report also emphasised the essential role of the Government and local authorities in redeveloping the national game.

After a disgraceful riot at an FA Cup match at Luton in March 1985, Margaret Thatcher summoned FA and League officials to Downing Street. Ted Croker, perhaps unwisely, said to the Prime Minister: “These people are society’s problem and we don’t want your hooligans at our sport”. The FA were given six weeks to produce a report. The idea of a national membership scheme for football was considered and a ban on the general sale of alcohol at grounds was set in motion.

It was Mr Justice Oliver Popplewell’s task to enquire into two numbing disasters that occurred within 18 days of each other in May of the same year. On the Bradford fire, which claimed 56 lives, he wrote: “Safety levels must be improved quickly. I am quite satisfied that the cause of the fire was the dropping of a lighted match, or a cigarette or tobacco on to debris beneath the floorboards”.

Popplewell’s recommendations called for more grounds to be designated under the Safety of Sports Grounds Act, the building of non-combustible stands, better evacuation procedures by police, tighter restrictions by the fire authorities, trained stewards and ‘suitable and adequate’ exits. His clear message was that the safety of the fans came before the interests of the clubs.

On Heysel, which claimed 39, he wrote: “I cannot too strongly or too frequently emphasise that if hooligans did not behave like hooligans at football matches, there would be no risk of such death or injury”. It meant another difficult meeting with the Prime Minister and a UEFA decision to ban all English clubs from European competition indefinitely. The Government promised tougher measures on alcohol, crowd limits, security and the powers of the police. Mrs Thatcher expected the FA to produce a membership card scheme ‘urgently’.

English football may have reached its lowest point but no-one in the game thought that such a scheme was the answer. Adapting grounds and setting up and maintaining the technology would be an awesome task. So would the processing of millions of applications and cards and replacing those which were lost or stolen. Delay at the turnstiles would surely cause frustration and trouble. It took another major disaster, Hillsborough, to end all thoughts of implementing it.

On 7 June 1988 it was announced that Graham Kelly, secretary of the Football League, would be replacing the retiring Ted Croker as chief executive of the FA. A month later the Council received a report at their Summer Meeting from a London firm of management consultants. This report, entitled ‘The Football Association: Organising for the Future’, had been commissioned by the FA and was meant to be an examination of “the top structure of the Association, including salaried staff, and its various relationships with Council”.

The report suggested that a more powerful FA chief executive should take his place on a Board of Management. The Council was said to be “out of touch with what is essentially a young person’s game…and too large and unwieldy to operate effectively”. It recommended that members should be under 62 when elected and should retire at 72. It also criticised the absence of “soundly formulated budgets and plans”.

The Council thought that several of its recommendations were worthy of further consideration but essentially the report was too radical.

Forty-eight hours after the tragedy at Hillsborough, the FA decided that the Cup should continue. The semi-final would be played at Old Trafford on 7 May. Graham Kelly understood the criticism that the FA were being ‘insensitive’ but it was imperative to make decisions so that everyone could make plans in the light of them. Liverpool went on to win the ‘Requiem Cup Final’ at Wembley and the crowd’s singing of ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’ was more poignant than ever.

England had a positive World Cup in Italy in 1990, reaching the semi-finals for their best-ever performance on foreign soil. The whole country had been gripped by the same kind of fever which afflicts some towns before a big FA Cup tie. English clubs were allowed back into European competition, Bobby Robson went to PSV Eindhoven in Holland and Graham Taylor, the new England manager, said that our good showing at Italia 90 was “something to build on”.

On 29 June 1991 the FA Council ratified a plan to set up an ‘FA Premier League’. Starting in the 1992-93 season, its long-term aim was to reduce the number of games for top players to help the England team and to take maximum advantage of the commercial opportunities that an elite league would bring.

The new ‘Premier Division’ would eventually be reduced from 22 to 18 clubs, with more clubs being relegated than were promoted. Then clubs would be promoted and relegated, providing the promoted clubs (from the old ‘Second Division’) met all the necessary criteria. ‘Premier’ clubs would need to have facilities even better than those required by the Taylor Report.

With the FA being responsible for the administration of the new league, the commercial benefits of uniting the FA Premier League, the FA Cup and the England team under one marketing banner were expected to be immense. These benefits would spread throughout the game, meaning more investment in stadium facilities and amenities and therefore a better deal for supporters.

The power struggle between the FA and the Football League was effectively at an end. The image and stock of the game was now better and brighter.

‘The Cup’, now around 120 years old, experienced some breaks with tradition around this time. Some semi-finals were played at Wembley, there were penalty shootouts at the end of drawn replays and Littlewoods Pools became the first sponsor, paying £14m over four years.

In 1995 the European Court of Justice upheld the ‘Bosman ruling’, barring transfer fees for players who were out of contract and removing the limit on the number of foreign players that clubs could field. ‘Football came home’ as the FA hosted the 1996 European Championship Finals and Terry Venables’ England team reached the semi-finals of a feel-good tournament.

Three years later, the FA bought Wembley Stadium, voted in favour of a streamlined 14-man Board of Directors and attracted criticism for allowing Manchester United to withdraw from the FA Cup to take part in the FIFA World Club Championship in Brazil.

But we have a world-class stadium at Wembley, completed in 2007 at a cost of around £800m. The 126th FA Cup Final, featuring Chelsea and Manchester United, was the first Final to be played there. A capacity crowd inside the stadium, 12.9m viewers on UK television and about 450m worldwide, saw a parade of Wembley winners from the last 50 years before the kick-off.

England met Brazil at the new stadium two weeks later. Manager Steve McClaren was replaced by the Italian Fabio Capello, England’s second foreign coach, after the team had missed out on qualification for EURO 2008. Roy Hodgson, who had previously managed three national teams as well as several club sides at home and abroad, was appointed Capello’s successor in May 2012.

The FA Skills programme, launched in 2007 for children aged five to eleven, went from strength to strength and had filled 3m places by 2012. The FA’s ‘Respect’ programme, started in 2008, was a response to a clear message from throughout the game that the health of football depended on high standards of behaviour on and off the pitch. It was to have a positive effect on referee recruitment and on-field dissent.

The ‘FA Women’s Super League’ was inaugurated in 2011 as a semi-professional league playing its matches during the summer months. It replaced the FA Women’s Premier League as the highest level of women’s football and started with eight clubs. The women’s game received a further boost when Team GB, managed by former England Women’s National Coach Hope Powell, performed before huge crowds at the London 2012 Olympic Games.

St. George’s Park, the FA’s new National Football Centre in Burton upon Trent, was opened in 2012. It will be a centre for coach education, a leading centre of sports medicine and science, and provide a training home for Club England and its 24 representative sides. An elite training pitch has been graded to exactly match the current surface at Wembley Stadium.

In 2013, the organisation celebrated its 150th anniversary with a string of events across the year, culminating in a glittering gala dinner at the Grand Connaught Rooms in central London on 26 October to celebrate the anniversary, back on the exact site where it all began in 1863.

The effects of SGP's introduction on the pitch soon began to show, as England teams across the board enjoyed greater tournament success than previously.

In 2015, the England Women's senior team recorded a best-ever performance at the FIFA Women's World Cup when they secured third place in Canada, after a 1-0 victory over Germany under the stewardship of Mark Sampson.

And the development teams began to shine, with Gareth Southgate leading his men's under-21 side to victory at the 2016 Toulon Tournament in France, before 2017 saw England men's under-20s and under-17s win their respective FIFA World Cups, along with an U19 EURO title and another victory in Toulon.

Following his success with the MU21s and the departure of Sam Allardyce as England senior manager, Southgate was elected to take charge of the Three Lions in 2016 and went on to change the approach and philosophy around the squad.

What followed saw Southgate's team reached the 2018 FIFA World Cup semi-finals in Russia, the first time they'd reached the last four since 1990, only to lose out in extra-time against Croatia.

Southgate continued to build a young and vibrant squad and they made history in 2021 when they reached a first-ever UEFA EURO Final when the tournament was held across multiple venues in Europe, culminating in the showpiece Final at Wembley where they faced Italy.

Despite leading through Luke Shaw's early goal, Italy fought back to equalise and take the game to extra time before the match finished 1-1 and went to a penalty shootout. Unfortunately for England, the Azzurri held their nerve to win the title but the signs of progress for England were clear to see.

The appointment of Sarina Wiegman as the new England women's head coach also heralded history for the Lionesses, as she oversaw a triumphant campaign in the UEFA Women's EUROs on home soil in 2022.

A former Netherlands head coach, Wiegman's team swept all before them in the competition en-route to the Final against Germany at an electric Wembley Stadium. Goals from Ella Toone and Chloe Kelly clinched a 2-1 victory and a first major title for the women's senior team to further boost the profile and movement of women's football across the country.

They followed that up in 2023 by reaching their first ever World Cup Final at the FIFA Women's World Cup in Australia and New Zealand, where they suffered heartbreak at the last hurdle following a narrow 1-0 defeat against Spain.

A year later, in the summer of 2024, Gareth Southgate's Three Lions reached the final for a second successive European Championship, but narrowly lost 2-1 against Spain in Berlin. Shortly after the final, Southgate resigned after eight years in the role and 102 games in charge, describing the job as the "honour of my life."

In August, Lee Carsley was appointed interim head coach of England senior men ahead of the start of the 2024-25 UEFA Nations League campaign.

The new England men's senior head coach was appointed in October 2024, with former Chelsea, Bayern Munich and Paris Saint-Germain manager Thomas Tuchel taking charge for the Three Lions' 2026 World Cup qualifying campaign.